|

Big Rear Brakes

The VHS rear brake conversion

|

Words and pictures: Rob Bell, with

thanks to Wayne Nation of VHS for his assistance in putting this

article together |

|

Introduction

Why have big brakes on your MG? If you had a properly set up brake system, you

could probably pull an F to a halt with discs the size of 50 pence pieces in

practically the same distance as the same car with discs the size of dinner

plates. Big brakes are heavy too – increasing unsprung weight. The way I look at

this, unsprung weight describes that mass of metal at the end of the axle – the

wheel, the tyre, the hub. The heavier this is, the harder the springs and

dampers have to work to keep them under control after bouncing over bumps. Lower

the unsprung weight, the easier it is to make a car handle and ride well. Big

brakes are also expensive – not least because you’re looking at much more

material being incorporated in them.

Big brakes can be a hazard.

Why on earth would anyone want big brakes? Putting aside marketing (go on, admit

it, you love the look of huge brakes behind those shiny alloys of yours!), big

brakes do have a purpose. It’s all about heat. While those 50pence-sized brakes

could probably lead to wheel locking just as effectively as a big brake, they’d

get so hot that they’d probably boil your brake fluid and probably ignite the

friction material on the brake pads. Brakes convert kinetic energy into heat –

and if you’re travelling fast, there may well be vast amounts of energy to

disperse! Big brakes have an advantage: their much larger surface area means

that they can shift much more heat in a much shorter period – which is ideal of

a high performance sports car that is being used heavily on the track or on the

road. But ultimately, they won’t stop your car any faster than an otherwise

identical, smaller disc-equipped car. That said, the greater braking leverage

that is to be gained from applying a retardation force at the edge of a larger

disc means that for any given brake-pedal movement, you will get more stopping

force applied. Unsurprising then that we all feel that big brakes mean more

stopping power – but this is a subjective impression, and not the reality.

The funny thing is, the ultimate limiting factor of the

rate of deceleration you get from brakes is not the braking system at all. It’s

the tyres! No matter how heavy or light the car, the braking force is limited

purely by how much grip your tyres can generate; the vehicle’s mass is simply

not part of the equation.

Why bother?

|

Stunning front AP racing 304mm front rotors

and red-painted, MG-logo'd 4-pot calipers. What's not to like? |

So why are we writing an article about big brakes in FTF?

Well, MG started it. They started fitting 304mm AP Racing 4-pot calliper brakes

to MGFs and then TFs. You have to agree that they do look sublime.

The odd thing was that they did absolutely nothing about

the rear discs. MG didn’t even bother altering the settings of the brake bias

valve.

Why should this matter? If the MGF and TF were a front

engine car, then actually it probably wouldn’t matter at all. In a 1G stop (the

same rate of change of velocity you’d feel if you’d jumped off a cliff edge), a

front-engine car would load up its front wheels due to weight transfer

effectively leading to 80 or indeed 90% of the work being performed by the front

wheels. An MGF is rather different. It’s weight distribution is rather more rear

biased (55% of the MG’s weight is over the rear wheels! [more]),

meaning that under the same circumstances, the rear brakes are still playing an

important role in slowing the progress of the car even during a 1G stop.

Estimates suggest that the split is something more like 60:40 front/rear under

these conditions. You can read more about this

here.

Which is where my problem with the big front brake kits comes in. When ever I

have driven cars fitted with the 304mm front disc, I have found that that is

just too easy to lock the front wheels – it’s as though the rears simply aren’t

pulling their weight in the stopping department. Given the mismatch in braking

torques between a 304mm and a 240mm disc, this perhaps is not surprising.

Frankly, a standard set up using race-bred pads all-round is far, far better

from this balance perspective.

Balancing out bigger front brakes

One solution for the big brake imbalance is to fit more

aggressive rear pads – say Mintex 1177 to Mintex 1144 at the front. But as

anyone who is familiar with the 1177 pad will testify, they eat discs, and cover

everything with tenacious pad dust… not ideal for a road car.

|

Top: before with standard sized 240mm rear

discs and bottom: the new VHS 280mm rear disc conversion. |

The only other solution is to fit a larger rear disc.

And given that 240mm discs look lost behind 16” wheels, there is an undeniable

aesthetic justification for going down this route too.

It is probably no coincidence that this yawning chasm of a gap in the market

has, until very recently, been left unfilled. Get your rear brakes wrong, and

you run the very real risk of dangerous over-braking of the rear wheels and

consquent rear lock up. Get rear-end lock up on entry to a corner, or even mid

corner, and you’ll be saying a big hello to the scenery (and everything that

Bill Oddy holds dear) as the rear of your MG goes hedge trimming. Dangerous.

Brake design is probably best left to the professionals.

One of the ironies of the collapse of MG Rover is the release of engineering

talent from the company into realms that hitherto it would never have

travelled; into the hands of the enthusiast market. The chassis development

team who worked with Rob Oldaker are a case in point. These guys have now set

up their own company (Vehicle Handling Solutions) and are producing kits for

MGF and TF owners. Find your TF too bouncy? They’ll do you replacement

Bilstein dampers in the specification that they wanted them in the first place

but weren’t allowed due to budget constraints. Want a better braking system

for your MG, then you’d better ask…

Which is what the MGF Register has done. And these guys

have come up trumps. And as you can see from the picture to the left, the

larger rear discs are worth fitting for the looks alone!

On the left is the standard-sized 240mm rear disc. On

the right, the new 266mm rear discs. They don’t look quite so puny any more do

they?

So you are interested in fitting these discs, how do you go about it?

What's required:

Tools required:

- vehicle jack and axle stands

- wheel brace

- socket set

- torque wrench

- set of Allen keys

|

|

Materials required:

- the VHS Big rear brake kit – approx 340 quid + VAT

|

|

Time required:

|

Instructions: How to fit the VHS rear

brake kit

|

1. |

First task is to move your car onto

solid level ground. As with MG’s ageless paraphrase goes,

safety first. First task is to move your car onto

solid level ground. As with MG’s ageless paraphrase goes,

safety first.

|

|

2. |

Now

raise the rear of the car up onto axle stands and remove the road wheels. Now

raise the rear of the car up onto axle stands and remove the road wheels.

With the road wheels removed, we can now gain access to the brakes

themselves.

|

|

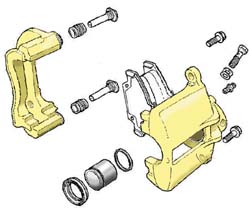

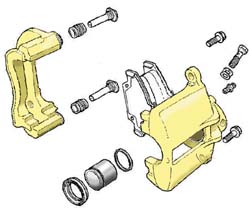

3. |

Disassemble

the brake carrier – there are two 8mm sliding bolts to undo – and once done

the outer pad carrier can be removed, along with the pad, as shown below. Disassemble

the brake carrier – there are two 8mm sliding bolts to undo – and once done

the outer pad carrier can be removed, along with the pad, as shown below. |

|

4. |

Next

remove the calliper, swinging it up and away and secure on some wire (an old

coat hanger is ideal for this). Next

remove the calliper, swinging it up and away and secure on some wire (an old

coat hanger is ideal for this). |

|

5. |

Next

identify remove the bolts retain the calliper to the hub carrier – in the

image to the right, we see that Wayne has already put a socket onto one of

the retaining bolts. Next

identify remove the bolts retain the calliper to the hub carrier – in the

image to the right, we see that Wayne has already put a socket onto one of

the retaining bolts.

Remove

both bolts, and remove the calliper carrier. Remove

both bolts, and remove the calliper carrier.

The removed

caliper carrier: The removed

caliper carrier:

|

|

6. |

Now remove the

discs – mine came off very easily as they had been replaced fairly recently

(oh well). The steps not shown here are removal of the two set-screws that

are fitted to help locate the disc to the hub, and the ‘gentle’ persuasion

required to release the disc from the hub – this may require some thumping

with a lump hammer, rotating the disc through 90 degrees between clouts to

release. Now remove the

discs – mine came off very easily as they had been replaced fairly recently

(oh well). The steps not shown here are removal of the two set-screws that

are fitted to help locate the disc to the hub, and the ‘gentle’ persuasion

required to release the disc from the hub – this may require some thumping

with a lump hammer, rotating the disc through 90 degrees between clouts to

release.Wayne made light work of these. I was

happy to take photographs… ;o)

|

|

7. |

Now clean up the

hubs with a wire brush to remove any loose rust or dirt from the hub

mounting surfaces. You’ll notice that the hub is nice and silver- that’s

because this was replaced very recently following a track day at Brands

Hatch; the bearing had completely failed – a known weak point in the MGF

chassis. Now clean up the

hubs with a wire brush to remove any loose rust or dirt from the hub

mounting surfaces. You’ll notice that the hub is nice and silver- that’s

because this was replaced very recently following a track day at Brands

Hatch; the bearing had completely failed – a known weak point in the MGF

chassis. |

|

|

Here

are two close up pictures of the rear wheel hub. On the left, you'll notice

that the centre locator spigot has a rounded appearance as it meets the

mating face of the hub. On the right is the other design, which is squared

of, and has an additional ridge. Thus, as can be seen, there are in fact

more than one design of hub – but they all share one part number as far as I

can make out and appear to be fitted randomly to either side of the vehicle

(for instance my car had both designs, differing from one side to the other

– which makes things very confusing! Here

are two close up pictures of the rear wheel hub. On the left, you'll notice

that the centre locator spigot has a rounded appearance as it meets the

mating face of the hub. On the right is the other design, which is squared

of, and has an additional ridge. Thus, as can be seen, there are in fact

more than one design of hub – but they all share one part number as far as I

can make out and appear to be fitted randomly to either side of the vehicle

(for instance my car had both designs, differing from one side to the other

– which makes things very confusing!

This becomes important on this big brake conversion,

as the central spigot is essential for locating the disc properly to the

wheel hub as we’ll see… |

|

8. |

But

first, yet more preparatory work with a wire brush! This time cleaning up

the hub carrier so that the calliper spacer/adapter plate can be fitted… But

first, yet more preparatory work with a wire brush! This time cleaning up

the hub carrier so that the calliper spacer/adapter plate can be fitted… |

|

|

You may find

that you need a metal file to get a nice, flat mounting surface – the end

result should be as neat as this… You may find

that you need a metal file to get a nice, flat mounting surface – the end

result should be as neat as this… |

|

9. |

Now

we come to the first part of the kit to be fitted – the calliper spacer

bracket – a nice piece of anodised steel… Now

we come to the first part of the kit to be fitted – the calliper spacer

bracket – a nice piece of anodised steel… |

|

|

And some of the

rest of the kit – the silver rings are aluminium disc locators – recall what

I was saying about the disc locating on that central spigot – this is where

these come in… And some of the

rest of the kit – the silver rings are aluminium disc locators – recall what

I was saying about the disc locating on that central spigot – this is where

these come in… |

|

|

And of course,

the big brakes themselves! They are re-drilled standard discs from the PSA

stable. The MGF PCD is established by slotting the existing mounting holes,

and two additional centring holes are also machined in the bell of the

discs. Nice work. When replacements are required, they’ll cost 80 quid plus

VAT… And of course,

the big brakes themselves! They are re-drilled standard discs from the PSA

stable. The MGF PCD is established by slotting the existing mounting holes,

and two additional centring holes are also machined in the bell of the

discs. Nice work. When replacements are required, they’ll cost 80 quid plus

VAT… |

|

|

Always

worth comparing new and old – the new discs are usefully larger than the

originals – just a shame they’re not slotted like the Rover Sport items I

was taking off… Always

worth comparing new and old – the new discs are usefully larger than the

originals – just a shame they’re not slotted like the Rover Sport items I

was taking off… |

|

10. |

This is the

clever bit. Whereas the standard disc locates to the outer edge of the

standard hub, the replacement discs centre on these adapter rings over the

centre bore spigot. Here’s Wayne offering up on of the adapter rings to this

hub. As mentioned earlier, there is more than one design of wheel hub – but

fortunately, the chaps at VHS are able to supply adapter rings to suit what

ever hubs you happen to have on your car – be they square shouldered, as

here or… This is the

clever bit. Whereas the standard disc locates to the outer edge of the

standard hub, the replacement discs centre on these adapter rings over the

centre bore spigot. Here’s Wayne offering up on of the adapter rings to this

hub. As mentioned earlier, there is more than one design of wheel hub – but

fortunately, the chaps at VHS are able to supply adapter rings to suit what

ever hubs you happen to have on your car – be they square shouldered, as

here or… |

|

|

…the

round-shouldered hub as pictured here (this happens to be the hub on the

opposite side of the car on my MGF - as mentioned above in point 7). …the

round-shouldered hub as pictured here (this happens to be the hub on the

opposite side of the car on my MGF - as mentioned above in point 7). |

|

|

The

ring adapter simply slides neatly into place. With the disc bolted in place,

it is sandwiched in place, so isn’t going to go anywhere! The

ring adapter simply slides neatly into place. With the disc bolted in place,

it is sandwiched in place, so isn’t going to go anywhere! |

|

11. |

Now we move

to the next stage: a nice cup of tea, and bolting the calliper carrier to

the spacer using the supplied counter-sunk screws… Now we move

to the next stage: a nice cup of tea, and bolting the calliper carrier to

the spacer using the supplied counter-sunk screws… |

|

|

One in, one more

to go… One in, one more

to go… |

|

|

…

and now the calliper can be mounted into its new position somewhat further

displaced from the centre of the hub than before. …

and now the calliper can be mounted into its new position somewhat further

displaced from the centre of the hub than before. |

|

12. |

Replacement

calliper carrier bolts are supplied with the kit – and here we can see the

assembly being bolted into position. Replacement

calliper carrier bolts are supplied with the kit – and here we can see the

assembly being bolted into position. |

|

|

Job done:

calliper carrier now securely bolted into place. Job done:

calliper carrier now securely bolted into place. |

|

13. |

Now we can

slide the new larger disc into place. Now we can

slide the new larger disc into place. |

|

|

The

retaining screws are now fitted to bring the disc into the correct position. The

retaining screws are now fitted to bring the disc into the correct position. |

|

|

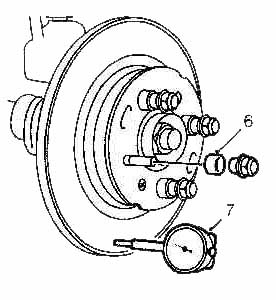

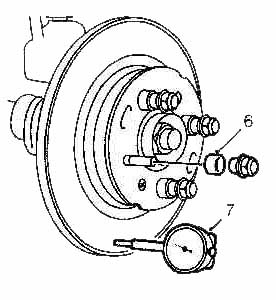

Disc rotated

through 360 degrees several times to ensure that there is no significant

‘wobble’ or ‘run-out’… You can use a dial position indicator (DPI, arrow 7

below) to ensure millimetric location precision. Disc rotated

through 360 degrees several times to ensure that there is no significant

‘wobble’ or ‘run-out’… You can use a dial position indicator (DPI, arrow 7

below) to ensure millimetric location precision.

|

|

14. |

Satisfied that

the disc is true when rotated, the calliper can be reassembled… First with

nice, new Mintex 1144 pads. Satisfied that

the disc is true when rotated, the calliper can be reassembled… First with

nice, new Mintex 1144 pads.

|

|

15. |

Before the

remainder of the calliper can be fitted, the piston needs to be screwed back

into its housing. Before doing this, remove the cap on the brake master

cylinder to ensure that there isn’t too much fluid already in the reservoir

– if there is, it may spill out over the paintwork and burn it off! Brake

fluid is a very effective paint striper… Before the

remainder of the calliper can be fitted, the piston needs to be screwed back

into its housing. Before doing this, remove the cap on the brake master

cylinder to ensure that there isn’t too much fluid already in the reservoir

– if there is, it may spill out over the paintwork and burn it off! Brake

fluid is a very effective paint striper… |

|

|

Once the

piston is screwed in (it moves clockwise – you can use any straight edge to

screw the piston into the calliper housing, or you can use a pair of pliers,

or you can even buy the Rover tool designed specially for the job!) Once the

piston is screwed in (it moves clockwise – you can use any straight edge to

screw the piston into the calliper housing, or you can use a pair of pliers,

or you can even buy the Rover tool designed specially for the job!)

Here Wayne finishes off the job – calliper now back in place. Perhaps we

should have given the calliper a lick of paint before refitting? You could

certainly do this when working on your own car.

|

|

16. |

Close up of the

completed disc and adapter assembly – it could almost be standard equipment

couldn’t it? Close up of the

completed disc and adapter assembly – it could almost be standard equipment

couldn’t it? |

|

|

And now

with the road wheel fitted, looking absolutely stunning. And now

with the road wheel fitted, looking absolutely stunning. |

Big

rear brakes fitted – worth doing?

Big

rear brakes fitted – worth doing?

The answer to this is definitely yes. Some would argue that

they’re worth fitting for the aesthetic value alone – those discs no longer look

lost behind 16” alloys in the way that the original 240mm items did. But that

wasn’t the reason for fitting them. The real proof of the pudding is on the road

and track – and I have to say that the brake balance with these discs is simply

brilliant. You can really heave on the middle peddle without fear of inducing

premature lock up of the front wheels – the rears also mean that the total

retardation is ultimately great than if you were braking using the front wheels

alone. And I am hopeful of additional benefits too – compared to my old brake

set up, I am hopeful that these discs will run a good deal cooler, which ought

to be good news in terms of brake disc and brake pad longevity, not to mention

the life span of the rear bearings themselves.

If you find yourself close to needing new rear discs and pads on your MGF/TF, I

would certainly recommend fitting these rear brakes. In the words of Tony the

Tiger: “They’re Grrrrrreat!”

First task is to move your car onto

solid level ground. As with MG’s ageless paraphrase goes,

safety first.

First task is to move your car onto

solid level ground. As with MG’s ageless paraphrase goes,

safety first.

Now

raise the rear of the car up onto axle stands and remove the road wheels.

Now

raise the rear of the car up onto axle stands and remove the road wheels. Disassemble

the brake carrier – there are two 8mm sliding bolts to undo – and once done

the outer pad carrier can be removed, along with the pad, as shown below.

Disassemble

the brake carrier – there are two 8mm sliding bolts to undo – and once done

the outer pad carrier can be removed, along with the pad, as shown below. Next

remove the calliper, swinging it up and away and secure on some wire (an old

coat hanger is ideal for this).

Next

remove the calliper, swinging it up and away and secure on some wire (an old

coat hanger is ideal for this). Next

identify remove the bolts retain the calliper to the hub carrier – in the

image to the right, we see that Wayne has already put a socket onto one of

the retaining bolts.

Next

identify remove the bolts retain the calliper to the hub carrier – in the

image to the right, we see that Wayne has already put a socket onto one of

the retaining bolts. Remove

both bolts, and remove the calliper carrier.

Remove

both bolts, and remove the calliper carrier. The removed

caliper carrier:

The removed

caliper carrier: Now remove the

discs – mine came off very easily as they had been replaced fairly recently

(oh well). The steps not shown here are removal of the two set-screws that

are fitted to help locate the disc to the hub, and the ‘gentle’ persuasion

required to release the disc from the hub – this may require some thumping

with a lump hammer, rotating the disc through 90 degrees between clouts to

release.

Now remove the

discs – mine came off very easily as they had been replaced fairly recently

(oh well). The steps not shown here are removal of the two set-screws that

are fitted to help locate the disc to the hub, and the ‘gentle’ persuasion

required to release the disc from the hub – this may require some thumping

with a lump hammer, rotating the disc through 90 degrees between clouts to

release. Now clean up the

hubs with a wire brush to remove any loose rust or dirt from the hub

mounting surfaces. You’ll notice that the hub is nice and silver- that’s

because this was replaced very recently following a track day at Brands

Hatch; the bearing had completely failed – a known weak point in the MGF

chassis.

Now clean up the

hubs with a wire brush to remove any loose rust or dirt from the hub

mounting surfaces. You’ll notice that the hub is nice and silver- that’s

because this was replaced very recently following a track day at Brands

Hatch; the bearing had completely failed – a known weak point in the MGF

chassis.

Here

are two close up pictures of the rear wheel hub. On the left, you'll notice

that the centre locator spigot has a rounded appearance as it meets the

mating face of the hub. On the right is the other design, which is squared

of, and has an additional ridge. Thus, as can be seen, there are in fact

more than one design of hub – but they all share one part number as far as I

can make out and appear to be fitted randomly to either side of the vehicle

(for instance my car had both designs, differing from one side to the other

– which makes things very confusing!

Here

are two close up pictures of the rear wheel hub. On the left, you'll notice

that the centre locator spigot has a rounded appearance as it meets the

mating face of the hub. On the right is the other design, which is squared

of, and has an additional ridge. Thus, as can be seen, there are in fact

more than one design of hub – but they all share one part number as far as I

can make out and appear to be fitted randomly to either side of the vehicle

(for instance my car had both designs, differing from one side to the other

– which makes things very confusing!

But

first, yet more preparatory work with a wire brush! This time cleaning up

the hub carrier so that the calliper spacer/adapter plate can be fitted…

But

first, yet more preparatory work with a wire brush! This time cleaning up

the hub carrier so that the calliper spacer/adapter plate can be fitted… You may find

that you need a metal file to get a nice, flat mounting surface – the end

result should be as neat as this…

You may find

that you need a metal file to get a nice, flat mounting surface – the end

result should be as neat as this… Now

we come to the first part of the kit to be fitted – the calliper spacer

bracket – a nice piece of anodised steel…

Now

we come to the first part of the kit to be fitted – the calliper spacer

bracket – a nice piece of anodised steel… And some of the

rest of the kit – the silver rings are aluminium disc locators – recall what

I was saying about the disc locating on that central spigot – this is where

these come in…

And some of the

rest of the kit – the silver rings are aluminium disc locators – recall what

I was saying about the disc locating on that central spigot – this is where

these come in… And of course,

the big brakes themselves! They are re-drilled standard discs from the PSA

stable. The MGF PCD is established by slotting the existing mounting holes,

and two additional centring holes are also machined in the bell of the

discs. Nice work. When replacements are required, they’ll cost 80 quid plus

VAT…

And of course,

the big brakes themselves! They are re-drilled standard discs from the PSA

stable. The MGF PCD is established by slotting the existing mounting holes,

and two additional centring holes are also machined in the bell of the

discs. Nice work. When replacements are required, they’ll cost 80 quid plus

VAT… Always

worth comparing new and old – the new discs are usefully larger than the

originals – just a shame they’re not slotted like the Rover Sport items I

was taking off…

Always

worth comparing new and old – the new discs are usefully larger than the

originals – just a shame they’re not slotted like the Rover Sport items I

was taking off… This is the

clever bit. Whereas the standard disc locates to the outer edge of the

standard hub, the replacement discs centre on these adapter rings over the

centre bore spigot. Here’s Wayne offering up on of the adapter rings to this

hub. As mentioned earlier, there is more than one design of wheel hub – but

fortunately, the chaps at VHS are able to supply adapter rings to suit what

ever hubs you happen to have on your car – be they square shouldered, as

here or…

This is the

clever bit. Whereas the standard disc locates to the outer edge of the

standard hub, the replacement discs centre on these adapter rings over the

centre bore spigot. Here’s Wayne offering up on of the adapter rings to this

hub. As mentioned earlier, there is more than one design of wheel hub – but

fortunately, the chaps at VHS are able to supply adapter rings to suit what

ever hubs you happen to have on your car – be they square shouldered, as

here or…  The

ring adapter simply slides neatly into place. With the disc bolted in place,

it is sandwiched in place, so isn’t going to go anywhere!

The

ring adapter simply slides neatly into place. With the disc bolted in place,

it is sandwiched in place, so isn’t going to go anywhere! Now we move

to the next stage: a nice cup of tea, and bolting the calliper carrier to

the spacer using the supplied counter-sunk screws…

Now we move

to the next stage: a nice cup of tea, and bolting the calliper carrier to

the spacer using the supplied counter-sunk screws… One in, one more

to go…

One in, one more

to go… …

and now the calliper can be mounted into its new position somewhat further

displaced from the centre of the hub than before.

…

and now the calliper can be mounted into its new position somewhat further

displaced from the centre of the hub than before. Replacement

calliper carrier bolts are supplied with the kit – and here we can see the

assembly being bolted into position.

Replacement

calliper carrier bolts are supplied with the kit – and here we can see the

assembly being bolted into position. Job done:

calliper carrier now securely bolted into place.

Job done:

calliper carrier now securely bolted into place. Now we can

slide the new larger disc into place.

Now we can

slide the new larger disc into place.

The

retaining screws are now fitted to bring the disc into the correct position.

The

retaining screws are now fitted to bring the disc into the correct position. Disc rotated

through 360 degrees several times to ensure that there is no significant

‘wobble’ or ‘run-out’… You can use a dial position indicator (DPI, arrow 7

below) to ensure millimetric location precision.

Disc rotated

through 360 degrees several times to ensure that there is no significant

‘wobble’ or ‘run-out’… You can use a dial position indicator (DPI, arrow 7

below) to ensure millimetric location precision.

Satisfied that

the disc is true when rotated, the calliper can be reassembled… First with

nice, new Mintex 1144 pads.

Satisfied that

the disc is true when rotated, the calliper can be reassembled… First with

nice, new Mintex 1144 pads. Before the

remainder of the calliper can be fitted, the piston needs to be screwed back

into its housing. Before doing this, remove the cap on the brake master

cylinder to ensure that there isn’t too much fluid already in the reservoir

– if there is, it may spill out over the paintwork and burn it off! Brake

fluid is a very effective paint striper…

Before the

remainder of the calliper can be fitted, the piston needs to be screwed back

into its housing. Before doing this, remove the cap on the brake master

cylinder to ensure that there isn’t too much fluid already in the reservoir

– if there is, it may spill out over the paintwork and burn it off! Brake

fluid is a very effective paint striper… Once the

piston is screwed in (it moves clockwise – you can use any straight edge to

screw the piston into the calliper housing, or you can use a pair of pliers,

or you can even buy the Rover tool designed specially for the job!)

Once the

piston is screwed in (it moves clockwise – you can use any straight edge to

screw the piston into the calliper housing, or you can use a pair of pliers,

or you can even buy the Rover tool designed specially for the job!) Close up of the

completed disc and adapter assembly – it could almost be standard equipment

couldn’t it?

Close up of the

completed disc and adapter assembly – it could almost be standard equipment

couldn’t it? And now

with the road wheel fitted, looking absolutely stunning.

And now

with the road wheel fitted, looking absolutely stunning. Big

rear brakes fitted –

Big

rear brakes fitted –